Tye Leung Schulze, Immigration Interpreter and Equal Rights Pioneer

Tye Leung Schulze was born in 1887, the eighth child in a working-class immigrant family in San Francisco’s Chinatown. She led a life of helping others and breaking barriers, despite facing considerable danger, discrimination, and poverty as a Chinese American woman in late 19th century America.

Through her later work as a translator, Tye Leung promoted human rights and fought human trafficking. She was also the first Chinese American woman to receive a federal appointment, the first to work in the federal immigration service, and the first to vote in a presidential election.

During the late 1800s, poverty and upheaval in China drove many Chinese immigrants, predominantly men, to seek opportunity in the United States. However, they often faced discrimination that made it difficult to earn a living.

Photo: Tye Leung Schulze in about 1908, photo courtesy of the California State Library.

The Chinese American immigrant community at the time also had a massive gender disparity. By one estimate, women made up fewer than 4% of Chinese immigrants in America in 1890. Combined with discrimination, poverty, and few rights for women, these conditions led to increased human trafficking and forced prostitution in Chinatown.

To feed their family of 12, Tye Leung’s father repaired shoes for $20 a month and her mother worked in a nearby boarding house. Some of Tye Leung’s earliest memories included asking for leftover food at San Francisco gambling dens. When she was nine years old, her parents sent her to work as a domestic servant for another family.

When she could, Tye Leung studied English at a local Christian missionary school. When she was 12, her parents arranged for her to marry an older Chinese man in Montana, but she refused and ran away to the mission house.

There, she helped the mission’s superintendent, Donaldina Cameron, free women and girls who were being held against their will in local brothels. Known for breaking down brothel doors with a fire ax, Cameron helped an estimated 2,000 people escape human trafficking. Cameron brought Tye Leung on brothel raids to translate for Chinese immigrants.

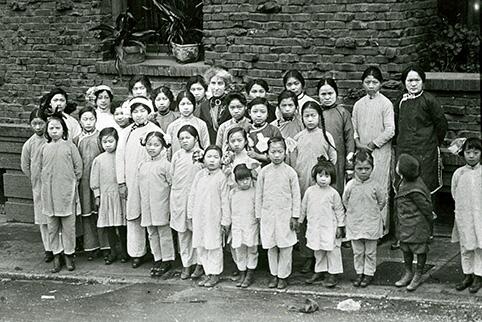

Tye Leung, second from left, back row, stands with a group of children and staff from the Presbyterian mission where she worked with Donaldina Cameron, center, a crusading anti-prostitution and anti-trafficking activist. Photo courtesy of the California History Room, California State Library, Sacramento, California.

In 1910, Tye Leung joined the staff of the newly opened Angel Island Immigration Station off the coast of San Francisco. She served as a translator and assistant to the matrons, who were responsible for overseeing female immigrants.

Tye Leung’s efforts were part of an extensive screening process created by the Chinese Exclusion Acts, which barred most Chinese immigrants from entering the U.S. Screenings could require multiple interviews and stretch over several days.

As a translator, Tye Leung helped inspectors as they attempted to distinguish female family members, who could lawfully enter the country, from those masquerading as immediate family members. Immigration Service staff barred suspected prostitutes from entering the country.

In 1912, shortly after California gave women the right to vote, newspapers reported that Tye Leung became the first Chinese American woman to vote in a presidential election. The San Francisco Examiner praised her vote in the Republican Party’s primary as a step toward “the complete enfranchisement of women” and the “lifting up of all the races of the earth.”

While working at Angel Island, Tye Leung met Charles Schulze, an immigration inspector and descendant of German immigrants. At just over four feet, Tye Leung was nicknamed “Tiny.” Schulze was more than six-feet tall. The two fell in love, but their parents disapproved of the match and interracial marriage was illegal in California. In 1913, they traveled to Washington state to get married.

Above: Angel Island in about 1910, soon after it opened as an entry and inspection point for immigrants arriving from the Pacific, especially Asian men and women facing limited entry and long detentions due to the Chinese Exclusion Acts. Photo courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

The marriage created a crisis for the couple at work. According to historian Judy Yung, they were pressured to leave their positions at the Immigration Bureau, and it took time for them to find new employment. Charles found a position working for the Southern Pacific Railway and Tye Leung studied bookkeeping and worked for the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company as an operator and translator on their Chinatown exchange. The couple had four children before Charles died in 1934.

Tye Leung worked for the Immigration and Naturalization Service as a translator again for a short period in 1946 after the War Brides Act of 1945 created a temporary surge in the immigration of Chinese women. Over the following decades, she continued working as a translator for the Chinese community in San Francisco until her death in 1972. She wrote, “During my life I do interpreting for Chinese people who needed my help . . . we are all human.”

Sources and further reading:

If you wish to learn more about Tye Leung Schulze, you can view a short film about her life created by PBS, with an informative interview on conditions in turn-of-the-century Chinatown with Julia Flynn Siler. The National Park Service and the historical collection Alexander Street offer biographical sketches of Tye Leung Schulze. Finally, for a broader view of women’s lives in Chinatown, as well as insights on Tye Leung Schulze, you can consult Judy Yung’s Unbound Feet: A Social History of Chinese Women in San Francisco, University of California Press, 1995.