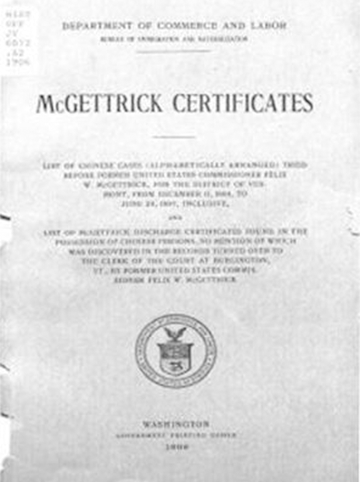

McGettrick Certificates

The USCIS History Office and Library has digitized and made available online the 1906 Bureau of Immigration publication McGettrick Certificates: List of Chinese Cases Tried Before Former United States Commissioner Felix W. McGettrick, for the District of Vermont, from December 11, 1894 to June 24, 1897, Inclusive, and List of McGettrick Discharge Certificates Found in the Possession of Chinese Persons, No mention of which was Discovered in the Records Turned Over to the Clerk of the Court at Burlington, Vt., by Former United States Commissioner Felix W. McGettrick.

The publication, not easily available until now, includes the names of roughly 1,000 Chinese migrants who entered the U.S. over the Canadian border south of Montreal during the mid-1890s. Each of the migrants listed claimed to be a U.S.-born citizen and the majority of them, after a hearing in front of U.S. Commissioner Felix W. McGettrick, received a “Certificate of Discharge” which could be used as proof of citizenship. Though many of these claims to citizenship were questionable, the list of McGettrick Certificates should be of interest to family historians whose Chinese ancestors entered the U.S. through Canada and anyone interested in the migration of Chinese to the east coast of the U.S.

Background

Between 1882 and 1943 the U.S. government severely restricted the legal immigration of Chinese migrants through a series of laws that became known as the “Chinese Exclusion Acts.” At first, the Chinese Bureau, within the Department of the Treasury, enforced the laws. In 1900 Congress transferred the supervision of exclusion laws to the Bureau of Immigration. The Bureau of Immigration, which eventually became part of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), enforced exclusion laws until they were repealed in 1943.

Under Chinese exclusion laws, Chinese laborers, who had previously been the vast majority of Chinese migrants, could not legally enter the U.S. Members of relatively small exempt classes of Chinese migrants – such as students, merchants and government officials – could enter the U.S., provided they had the proper documents to support their exempt status. U.S.-born citizens of Chinese descent also had the right to reenter the U.S. after trips abroad, as long as they could prove their citizenship.

The right of re-entry for native-born U.S. citizens of Chinese descent was an important, and at the time rare, recognition of Chinese Americans’ civil rights. It also, however, provided a loophole through which non-native-born Chinese migrants could attempt to enter the U.S.

In the years around 1900 some Chinese migrants tried to evade exclusion restrictions by first traveling to Canada and then entering the U.S. across the northern border. While most Chinese migrants arrived on Canada’s west coast, the Canadian Pacific Railway provided them with the option to travel across the country to the east coast where enforcement of Chinese exclusion was believed to be less stringent.

At the border, Chinese migrants could cross into the U.S. secretly and hope to remain undetected while in the U.S. Or, they could get arrested by government officials and then demand a hearing in court to prove their U.S. citizenship. If the court agreed with a migrant’s claim of citizenship it would issue a “Certificate of Discharge” or “Commissioner’s Certificate,” which the migrant could then use as proof of citizenship.

(Note: The “Commissioner” in this instance refers to a federal court commissioner – a type of federal judge – and not a U.S. Commissioner of Immigration.)

Chinese migrants and their attorneys quickly learned which courts were likely to issue Certificates of Discharge. Some judges and commissioners held the government to high standards in proving its cases against migrants; others held sympathetic humanitarian beliefs; and many simply accepted bribes.

Felix W. McGettrick was one such commissioner. During his short tenure as commissioner at St. Albans, Vermont, from March 1894 to July 1897, McGettrick tried and discharged at least 1,100 Chinese migrants, most of who claimed U.S. citizenship. McGettrick denied any wrongdoing and was never charged with any crime, but the high volume of cases he heard and his extreme leniency in deciding them suggest otherwise.

At the very least, McGettrick kept poor records. He did not keep a docket and claimed that records from at least 300 discharge cases were stolen from him. Additionally, McGettrick admitted to providing multiple Certificates of Discharge to some Chinese migrants, which likely contributed to document fraud.

Sometimes, multiple migrants reused the same certificate or forged Commissioner McGettrick’s signature and seal, leading to additional fraud. It is unknown how many of the Chinese migrants who possessed McGettrick Certificates were actually U.S. citizens.

By 1905, the Bureau of Immigration had come across so many McGettrick Certificates that it decided to create a list of the known certificates bearing McGettrick’s signature. The Bureau hoped to determine both the number of certificates McGettrick had actually issued and the number of forged certificates. The list would also allow the Bureau to identify cases of fraud in which two individuals had submitted certificates with similar or identical information. These cases would be flagged for investigation.

The resulting document was printed in 1906 and distributed to immigration, customs, and State Department officials. It included a list of cases tried before Commissioner McGettrick, from December 11, 1894, to June 24, 1897. It also included a shorter list of McGettrick Certificates found in the possession of Chinese persons for which there was no mention in McGettrick’s records.

The lists are arranged alphabetically, using English versions of the Chinese names. They also contain whatever information was available from McGettrick’s incomplete records, such as date of arrest, date of hearing, names of witnesses, claimed place of birth, place of residence, and a physical description. Most entries contain only partial information.

The lists include Chinese migrants who entered the U.S. over the Canadian border south of Montreal, during the mid-1890s. Boston, Providence, and other areas of New England are the most common places of residence listed, and the majority of migrants claimed the west coast of the U.S. as their place of birth. Links to the full text of the lists are available from the USCIS History Library Catalog.